The God Kings Of Uru [continued]

Another kilometre further north brought me to a tree-covered hilltop. Ahead of me, towering above the trees, stood a gigantic formation of granite monoliths.

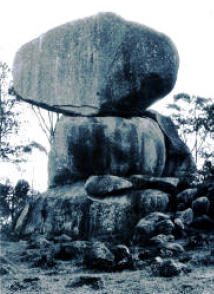

The formation was definitely man-made, consisting of three massive boulders, placed against one another in such a way as to form two caverns. Atop these boulders rests another huge rock, which together with two of the upright boulders, when viewed from the west and south-west, presents the appearance of a huge phallic symbol.

The structure rests upon a monstrous, flat granite slab 2m tall by about 24m long, the entire slab measuring 118m in circumference. It stands on an north-south axis, with the upright ‘phallic’ stone formation at the southern end of the base slab.

The upright and ‘capstone’ phallic formation boulders measure 23.3m in circumference by 9.2m tall, and including the base slab height above ground level, the entire structure stands 11m tall.

Adjoining the western side of the upright boulders are three smaller rocks arranged upon the base slab so as to form a wall, behind which a small group of worshippers might gather.

This phallic-shaped structure closely resembles tomb-temples found across Asia, Western Europe and the British Isles.

Two caverns had been sealed with granite rubble walls; the first [western side] cavern having been open at both ends. The walls for these had collapsed with the passing of time.

Here was a tomb large enough inside for the internment of an adult body with space for any tomb goods [now vanished]. However, there were no signs of human remains, as granite country seldom preserves bones. Nearby, the east cavern had only one small narrow opening. Could it have held the remains of a child?

Photo Left: Close-up of the topmost overlying stone.

Photo copyright © Rex Gilroy 2004.

Photo Right: The Tomb consists of a large cavern between

two massive boulders, large enough to hold a

body and burial offerings once sealed at both

ends, and a small sealed crevice nearby

perhaps once used to contain the remains of a

baby or young child. As granite country does

not preserve human remains none survive

here.

Photo copyright © Rex Gilroy 2004.

|

Then as I stood peering over what remained of the rubble wall of the larger tomb’s southern opening, I happened to look down to see weathered, engraved glyphs beneath my feet. They read:

“The tomb of Namou. Gather and mourn here.”

Thus, about 5km north of the “mourning stone” bearing his name, I had stumbled upon the tomb of this monarch; a true God-King who must have held considerable power over the New England region, if not elsewhere, as evidenced by the impressive monolithic tomb raised for him, the construction of which required the transportation and erection of these massive stones with whatever means, by a great number of workers.

For each of the stones, weighing at least 40 tonnes, including the massive platform [which together with its buried portion would easily weigh around 1,000 tonnes], were not natural to the site, having been dragged from an area about 1km distant.

The Moonbi Range culture centre would have been served by a considerable population, for an army of workers would have been needed to raise the tomb of Namou, and other massive granite structures hereabouts.

These activities required not only planning by an organising body, a priestly caste of artisans and astronomer-mathematicians, but also the overall ruling class undoubtedly backed up by an army of warriors, and this would have been the case among all the widely-distributed Uruan colonies throughout Australia. Therefore the tomb of Namou is a symbol of the power wielded by the Kings of Uru. Individual monarchs of truly God-King status ruled over kingdoms of large extend, which sub-divided Australia in much the same way as Aboriginal tribal boundaries once did.

Despite the vast distances, trade expeditions, both overland and on the inland rivers, as well as sea voyages, extended contacts between the far-flung isolated kingdoms.

Possibly the Uruan written language was developed somewhere in eastern Australia from where it was spread across the continent through trade. By this means also new astronomical, technological and other information was exchanged.

The God-Kings of Uru grew in power through these stone-age trade activities, which included islands beyond Australia. The ‘Serpent Warriors’ [see Chapter Eight] of the Moonbi Range culture centre were probably an elite guard of the kings of the New England ‘kingdom’, and would have had their counterparts elsewhere across Australia; the military might with which these monarchs kept control over their subjects, the labour force expected to construct the megalithic monuments. Power struggles had to have existed; territorial conflicts and mining disputes.

The God-Kings of Uru monopolised the territories they ruled; territories that contained rich deposits of ochre, chert and other rock needed for tool and weapon manufacture; all of which were highly prized for trade.

Indeed, the earliest wars of Stone-Age people were fought for the possession of ochre and chert mines; just as much later they would be fought over mineral-bearing territories across the earth.

Tomb Of Namou

Tomb Of Namou

Uruan City Of Ikaria

Uruan City Of Ikaria Uruan Swastika

Uruan Swastika Nim Face

Nim Face